Western

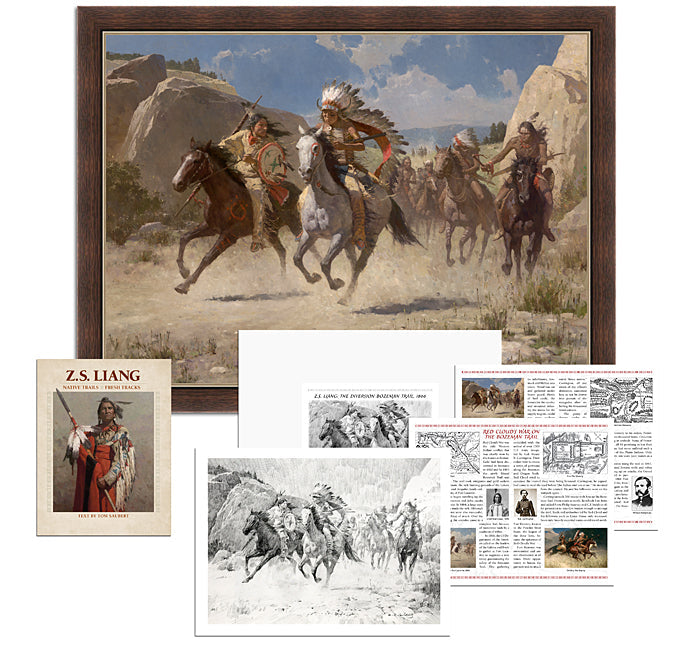

The Diversion, Bozeman Trail, 1866

Z.S. Liang

Low stock

Couldn't load pickup availability

Limited Edition of: 25 / 15

Details

Details

Red Cloud’s War was the only Western Indian conflict that was clearly won by the American Indian. Gold had been discovered in Montana in 1862 and by 1863 the newly blazed Bozeman Trail was the most direct route to it. The trail took emigrants and gold seekers through the Powder River Basin, the rich hunting grounds of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho, lands ceded to them by the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

The first emigrant trains began traveling up the trail not long after John Bozeman and John Jacobs had finished marking the route. In 1864, a large train of 2,000 settlers successfully made the trek. Although some additional wagon trains were also successful, they were under constant threat of attack. Over the next two years, travel along the corridor came to a complete halt because of numerous raids by a coalition of tribes.

In 1866, the US Department of the Interior called on the leaders of the Lakota and Brule to gather at Fort Laramie to negotiate a new treaty guaranteeing the safety of the Bozeman Trail. This gathering coincided with the arrival of over 1300 U.S. Army troops, led by Col. Henry B. Carrington. Their orders were to create a series of garrisons along the Bozeman and Oregon Trails. Red Cloud tried to convince the council they were being betrayed. Carrington, he argued, had come to steal the road before “the Indian said yes or no.” He stormed from the council. He and his followers were on the warpath again.

Carrington took 700 troops with him up the Bozeman Trail. From south to north, he rebuilt Fort Reno and added Forts Philip Kearney and C.F. Smith to offer protection to travelers brazen enough to attempt the trail. Raids and ambushes led by Red Cloud and his followers such as Crazy Horse only increased. Soon only heavily escorted trains could travel north. Fort Kearney, located in the Powder River Basin, the largest of the three forts, became the epicenter of Red Cloud’s War.

Fort Kearney was surrounded and under observation at all times. Every opportunity to harass the garrison and to attack its inhabitants, livestock and lifeline was taken. Wood was cut and gathered under heavy guard. Herds of beef cattle, the horses for the cavalry and mounted infantry, the mules for the supply wagons, could not graze without protection. The rich game country around the fort could not be hunted. There was no certainty about the attacks, except an assurance that one was always due at any given moment.

One tactic often used by the Indians against the soldiers during the many skirmishes, was a decoy feint. This involved sending a small group of fighters against a larger company of soldiers who would fight off this small group and give pursuit. The retreating warriors were actually a decoy to lure the soldiers into a surprise trap made up of superior numbers of Indians waiting to envelop them.

None was more successful and tragic than that of December 21, 1866. The day’s wood-cutting party had come under attack outside the fort. A detachment of 80 men was gathered to ride to their aid. Just as they were to leave Captain William J. Fetterman attached himself to the column and, as the ranking officer, took command. New to the frontier, but famously arrogant, he had previously claimed that “with 80 men he could ride through the entire Sioux nation.'' Carrington, all too aware of the officer’s demeanor, cautioned him to not be drawn into pursuit of the renegades after relieving the threatened wood-cutters.

The group of decoys, under the leadership of Crazy Horse, broke off their attack on the wood-cutting train with Fetterman’s approach. Contrary to his orders, Fetterman pursed. As many as two thousand Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho were waiting in ambush. None of Fetterman’s command survived, all 81 perishing in less than 30 minutes. The U.S. Army had never suffered such a great defeat at the hands of the Plains Indians. Only the Battle of Little Big Horn, ten years later, stands as a greater defeat.

With few if any emigrants using the trail in 1867, the army sequestered behind fortress walls and tribes showing few signs of easing up on attacks, the United States government decided to pursue a peace policy. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty recognized the Powder River Country once again as the hunting territory of the Lakota and their allies. A presidential proclamation was issued to abandon the forts. When the soldiers departed, Red Cloud’s warriors burned each to the ground. The Bozeman Trail was history.

Share

View full details